Day 1

Conversations That Set the Tone

By the time the first notes of Carnatic music carried across Hotel Clarks Amer, the Jaipur Literature Festival had already found its rhythm. Courtyards were filling slowly, winter sunlight filtering in, conversations beginning even before the first session formally opened.

Now in its 19th edition, the Jaipur Literature Festival 2026, presented by Vedanta and produced by Teamwork Arts, opened with the confidence of a gathering that knows exactly who it is. Running until 19 January 2026, the Festival brought together writers, thinkers, historians, poets, politicians, and cultural voices from across India and the world—five days where ideas are not just exchanged, but examined.

From its opening moments, Day One set the tone for what followed: thoughtful dialogue, rigorous debate, and a rare willingness to sit with complexity rather than rush toward conclusion.

Morning Music and the Art of Arriving

The day began with the Festival Morning Music, supported by Infosys Foundation. Carnatic vocalists Aishwarya Vidya Raghunath and Rithvik Raja, leading a five-piece ensemble, offered a performance that unfolded with deliberation rather than display. Accompanied by Sayee Rakshith on violin, Praveen Sparsh on mridangam, and Skanda Manjunath on ghatam, the music created a contemplative pause—less a prelude, more an invitation to listen closely.

It was the kind of opening that gently recalibrated attention, reminding listeners that Jaipur begins not with declarations, but with listening.

Opening Addresses: A Festival Aware of Its Own History

The formal inauguration followed with keynote remarks by Banu Mushtaq, alongside addresses from Festival Co-directors Namita Gokhale and William Dalrymple, and Festival Producer Sanjoy K. Roy. A traditional lamp-lighting ceremony marked the opening in the presence of Rajasthan’s Hon’ble Chief Minister Bhajan Lal Sharma, and Deputy Chief Ministers Diya Kumari and Prem Chand Bairwa.

As Sanjoy K. Roy reflected on the Festival’s journey—from its early years at Diggi Palace to its current global presence across nine cities—it became clear how organically Jaipur has absorbed this scale. The Festival has grown outward, but it has not lost its instinct for relevance, engaging openly with contemporary shifts, from artificial intelligence to evolving political and cultural landscapes.

Namita Gokhale’s welcome felt unmistakably Jaipur—light in tone, layered in meaning. Speaking of the month of Magh, of sunlight and kites stretching skyward, she captured the Festival’s temperament: curious, contradictory, opinionated, and playful. William Dalrymple, reflecting on nineteen years of growth, distilled the Festival’s success simply—sometimes half a million people turn up just to hear writers talk about books. Few literary gatherings anywhere in the world can make that claim without irony.

In his keynote address, Chief Minister Bhajan Lal Sharma spoke about Rajasthan’s cultural inheritance, describing the Jaipur Literature Festival as more than an event—a meeting ground of ideas and cultures. Sitting in the audience, it felt less like a line and more like a lived reality.

Writing as Necessity

The opening session featured International Booker Prize winner Banu Mushtaq in conversation with Moutushi Mukherjee. Mushtaq spoke with restraint and precision, framing writing as an act of survival and resistance in societies shaped by inequality and erasure. Literature, she insisted, is not separate from life—it is shaped by it, and accountable to it.

When she addressed young writers in the audience, her advice cut through the abstraction. “Don’t just plan writing. Start writing. Write, write, and write.” It was less instruction than reminder, grounded in experience rather than aspiration.

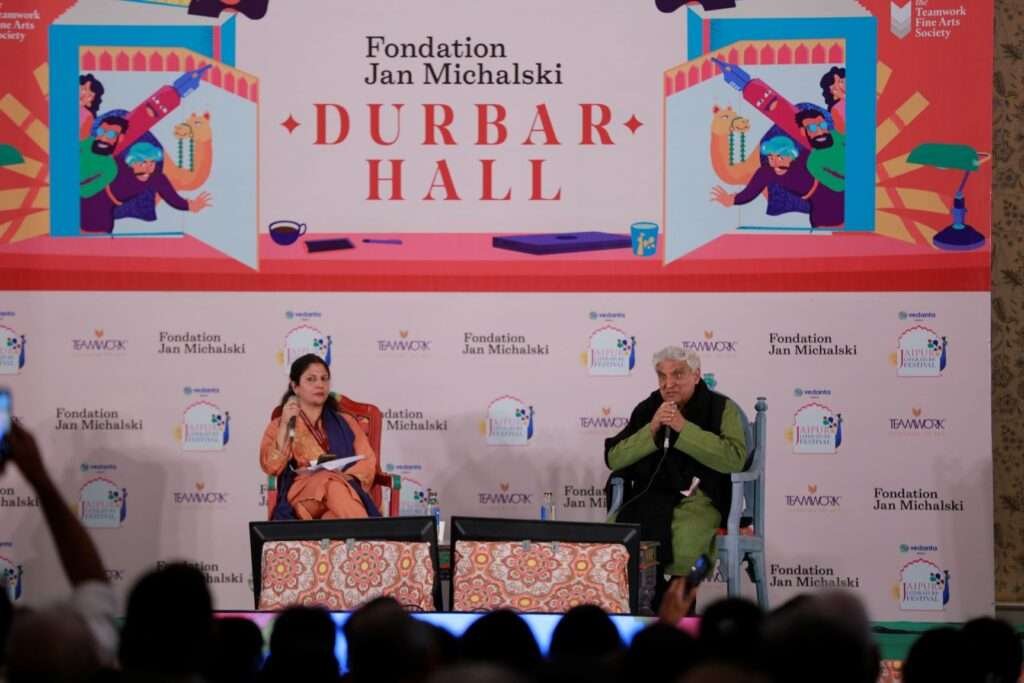

Javed Akhtar and the Ethics of Perspective

The energy shifted—but did not dissipate—with Javed Akhtar: Points of View, in conversation with Warisha Farasat. The audience filled every available space, drawn by Akhtar’s ability to balance humour with gravity. Reflecting on post-Independence India, the evolution of the middle class, and the role of writers in public life, he spoke without nostalgia or defensiveness.

To the many young listeners present, his words were quietly bracing: there will always be people better than you. The real work, he suggested, begins when comparison gives way to self-examination.

Histories in Conversation

Global histories and shared futures formed the centre of Coexistence: How Arabs and Jews Can Live Together, featuring historians Ussama Makdisi, Noa Avishag Schnall, and Avi Shlaim, moderated by William Sieghart. The conversation resisted neat resolution, instead tracing how memory, trauma, and narrative shape political possibility. It was a session marked by nuance—measured, at times uncomfortable, and necessary.

Loneliness, Craft, and the Interior World

One of the day’s most quietly compelling sessions was The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, where Kiran Desai spoke with Nandini Nair about her Booker-shortlisted novel. Desai reflected on creative discipline, emotional patience, and the long gestation periods that fiction often demands. The discussion moved fluidly between craft and solitude, touching on loneliness not as absence, but as texture—something that shapes characters, choices, and voice.

India’s Moral Memory

Later in the afternoon, Gopalkrishna Gandhi, in conversation with Narayani Basu, offered one of Day One’s most reflective moments in The Undying Light: India’s Futures. Drawing from his memoir The Undying Light: A Personal History of Independent India, Gandhi spoke about truth, integrity, and the discipline of honesty—both in public life and on the page.

His recollections of M.S. Subbulakshmi—her private sorrow, her public sublimity—lingered long after the session ended, underscoring how individual lives often illuminate national histories more powerfully than timelines ever can.

Books, Media, and Cultural Memory

The First Edition book launches added rhythm to the day. A Statesman and a Seeker: The Life and Legacy of Dr Karan Singh by Harbans Singh was launched by Namita Gokhale, William Dalrymple, and Sanjoy K. Roy, followed by a conversation between the author and Dr Karan Singh, moderated by Ravi Singh.

In a lighter register, Shalini Passi spoke with Ruchika Mehta about The Art of Being Fabulous, reflecting on creativity, self-expression, and contemporary culture. Meanwhile, Tom Freston, MTV co-founder, took the audience across decades and continents in Unplugged: Adventures from MTV to Timbuktu, recounting stories from the early days of global media—long before algorithms began shaping attention.

Trust in the Age of Information

The day closed with The Seven Rules of Trust, featuring Jimmy Wales, founder of Wikipedia, in conversation with Anita Anand. Addressing misinformation, transparency, and the role of digital platforms, Wales spoke candidly about how social media algorithms amplify hostility by rewarding outrage. Yet his outlook remained cautiously hopeful—history, he noted, suggests that societies can manage difference when systems are perceived as fair.

Anita Anand and Jimmy Wales